Sailor Jerry: The Blueprint of Rebellion

If American Traditional tattooing has a backbone, it’s made of bold lines, black ink, and the stubborn will of Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins. He didn’t just put pictures on skin—he forged an ethic: work hard, speak straight, and honor the craft even when the world looks down on it. Long before tattoos were brand currency, Collins was setting standards that modern shops still chase: cleaner needles, clearer pigments, sharper designs, and a code that said excellence matters more than approval. He’s the reason the anchor still carries weight, the pin-up still winks with menace, and the eagle still looks like it’s about to take your hand off.

Ghost & Darkness believes in that code. This isn’t a nostalgia act. It’s a transmission—lineage moving forward.

The Boy Who Wouldn’t Sit Still

Norman Keith Collins was born January 14, 1911, in Reno, Nevada. As a kid he didn’t gravitate toward straight lines or soft landings; he chased freight trains, learned to hand-poke tattoos, and found mentors the way hungry people find kitchens. “Big Mike” from Palmer, Alaska taught him hand poking; later, Chicago legend Gib “Tatts” Thomas put a machine in his hands and told him to get to work. Collins joined the U.S. Navy at 19 and saw the world the hard way—salt in the air, ports that smelled like steel and diesel, and the kind of sailors who wanted tattoos that meant something when the ship disappeared over the horizon.

That wandering mattered. It sharpened his eye and widened his vocabulary. Southeast Asia, Japan, Pacific ports—everywhere he went he collected images and attitude. Eventually, like iron filings to a magnet, he settled where the sailors were thick and the stories thicker: Honolulu.

Honolulu, Chinatown: Where the Lines Got Bold

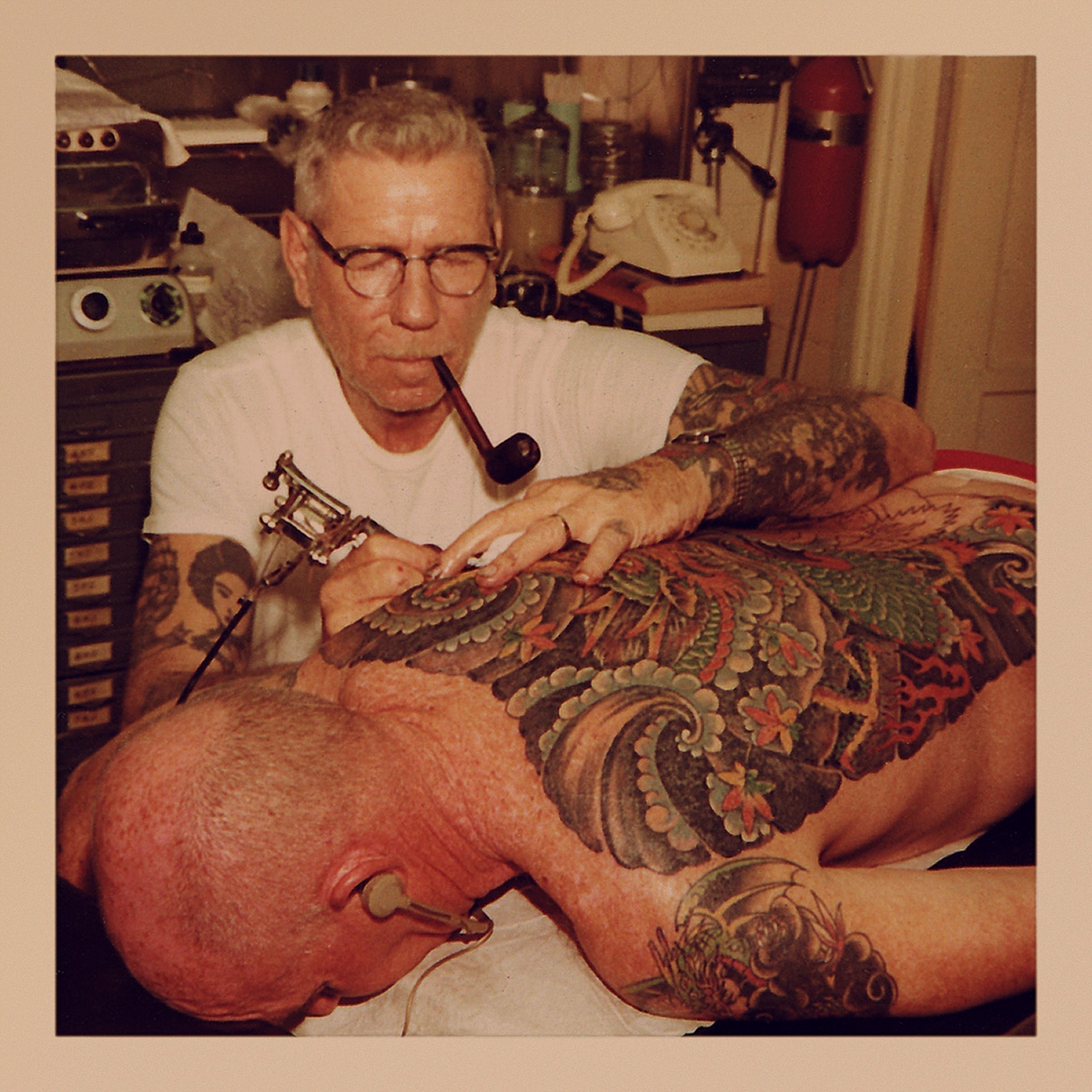

By the 1930s Collins was working in Hawaiʻi, and after the war the center of gravity became 1033 Smith Street in Honolulu’s Chinatown. That address is still sacred ground; today it’s Old Ironside Tattoo—officially recognized as Sailor Jerry’s shop and, for a period after his death, known as China Sea Tattoo. Walk past the door and you’ll feel it: the hum of machines, the grit under the paint, the sense that rules were written here.

Collins ran the place like a ship. Standards were high. Bullshit stayed outside. Inside, you got the real thing: clean work, tough images, lines that will outlast the man who wears them.

What “Sailor Jerry Style” Actually Means

People throw “American Traditional” around like it’s a mood. To Collins, it was engineering.

- Readability at distance. Thick outlines, confident black, tapered points. An eagle should read as an eagle from across a bar—no squinting.

- Curated palettes. He didn’t use every color in the crayon box. He pushed strong reds, yellows, greens, and blues that played well together and held up in sun and salt.

- Designed for the body. The shapes travel with the muscle. Look at a dagger on a forearm or a panther on a calf—the flow isn’t accidental.

Behind all of that were innovations most customers never saw. Collins mixed his own pigments to achieve stable, saturated colors that healed clean. He developed needle groupings to embed ink with less trauma. And at a time when safety standards were often an afterthought, he was early to single-use needles and autoclave sterilization—bringing hospital-grade thinking into a street shop. That doesn’t sound romantic, but it changed everything: better healing, fewer infections, more trust, and proof that a tattoo shop could be as professional as any clinical room if the artist gave a damn.

The Pacific Bridge: Letters Across an Ocean

Collins wasn’t an island unto himself. In the 1960s he began corresponding with Japanese masters, particularly Horihide. What started as letters grew into an exchange: American color techniques and inks flowing one way; Japanese composition, motifs, and philosophy flowing the other. They eventually met and traded ideas in person, accelerating a cross-pollination that pushed both traditions forward—bold Western iconography sharpened by Japanese placement and storytelling. You can see it in the dragons, the peonies, the windbars sneaking into the edges of hard American flash. That dialogue is one reason Traditional feels so alive today.

The Imagery: Why It Still Hits

Anchors. Not clip-art; commitments. An anchor says you’ve chosen your ground and you’re not drifting.

Pin-ups. Not cheesecake; talismans. Sailors wore luck on their skin before they wore it around their necks.

Eagles. Not mascots; oaths. They mark service, sacrifice, and the right to fly your own flag.

Daggers, tigers, ships, snakes. All of it says the same thing: you know danger, you’ve met it, and you’re still here.

Sailor Jerry’s economy was the revelation. Fewer lines, more meaning. A small vocabulary—endless sentences.

Rigging the Shop: Ethics and Attitude

Collins played sax. He hosted a radio show as “Old Ironsides.” He wrote, argued, and wasn’t shy about politics or calling out nonsense when he heard it. The personality mattered because it leaked into the work: uncompromising, occasionally abrasive, allergic to mediocrity. He ran a place that expected excellence—from himself first, then from anyone who wanted to pick up a machine under his roof. The shop wasn’t a clubhouse; it was a workshop where craft came before cool.

That discipline is part of why his flash sheets still move. You can copy an image. It’s harder to copy a standard.

Death, Legacy, and a Door That Still Opens

Norman Collins died in Honolulu on June 12, 1973, and is buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. But the address kept breathing. The shop at 1033 Smith Street remained a destination, a living archive where new hands measure themselves against old ghosts. Pilgrims still make the walk, still look up at the sign, still listen for the hum. Some places don’t fade; they dim and then burn again.

The Code Lives On (Whether You Like It or Not)

Here’s the real inheritance:

- Professionalism over posturing. Clean rooms, sterilized tools, and respect for the client are non-negotiables—not marketing copy.

- Design for the body. Tattoos should move like muscle and endure like bone.

- Earn your vocabulary. Every symbol means something, or it doesn’t belong.

- Trade with equals. The letters with Horihide weren’t fanmail—they were a two-way street. Iron sharpening iron across an ocean.

This is why his work still sells books, fills museums, and—most importantly—keeps getting tattooed. Because it’s not a trend; it’s a standard.

Wearing the Ethic (Ghost & Darkness)

We build clothes the way Collins built flash: bold, legible, durable. You can see the lineage in our lines—eagles that look ready to cut the sky, daggers you can feel in your ribs, snakes that coil with actual intent. American Traditional isn’t just the inspiration; it’s the engineering spec.

- Heavy fabrics that hold print like skin holds ink.

- Limited runs—because scarcity sharpens meaning.

- Art first: designs drawn by artists who understand symbolism, not just style.

You’re not buying a tee. You’re committing to a code the old man would understand.

If You Make the Pilgrimage

If you ever get to Honolulu, carve out time for Old Ironside Tattoo at 1033 Smith Street. Step through the door and keep your voice down. You’re in a place where craft outran fashion. Where a man spent his life proving that good work isn’t loud—it’s just good.

Dates, Addresses, and the Paper Trail (for the skeptics)

- Norman Keith Collins (Jan 14, 1911 – Jun 12, 1973), born Reno, Nevada; died Honolulu, Hawaiʻi.

- Last shop: 1033 Smith Street, Honolulu (now Old Ironside Tattoo; formerly China Sea Tattoo).

- Safety & craft innovations: custom pigments, needle configurations; early adoption of single-use needles and autoclave sterilization.

- Correspondence & exchange with Japanese master Horihide helped fuse American color with Japanese composition.

By Rob DPiazza — tracking the stories etched into life, culture, and skin.